CQ I-1

How is headache classified and diagnosed?

Recommendation

Headache should be classified and diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (beta version).

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

In 2004, the International Headache Society (IHS) revised the first edition of the IHS guideline for the first time in 15 years, incorporating the latest advances in research, evidence and criticisms. The resulting document, International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-2) was published in Cephalalgia.1) In the same year, the ICHD-2 was translated into Japanese and published.2) From 2004, headache should be classified and diagnosed in accordance with the ICHD-2.

The first recorded classification of headache was by Aretaeus (a physician born in 81 BC) of Cappadacia in the present day Turkey, who classified headaches into cephalalgia, cephalea, and heterocrania.3)-5) Heterocrania was described as “half head” headache, which is equivalent to migraine in the present day classification.

The first consensus-orientated headache classification in history was the classification by the Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache of the American Neurological Association (Ad Hoc classification) published in 1962.6) In this classification, headache was classified into 15 types, but no diagnostic criteria were included.

In 1988, the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society chaired by Olesen proposed the first international classification of headache disorders (IHS Classification, 1st edition, 1988).7) The IHS Classification 1st edition first classified headache into 13 items, and further subdivided into 165 headache types. For each subtype, operational criteria were described. Since the IHS Classification 1st edition placed greater weight on the nervous system rather than the vascular system as the mechanism of migraine development, the concept of vascular headache was abandoned. Migraine and cluster headache were classified independently, and muscle contraction headache was renamed tension-type headache.

When the IHS Classification 1st edition was tested on 740 persons, only 2 persons (0.3%) had unclassifiable headache, verifying that the classification covers the vast majority of headaches.5) The consistency, reproducibility and reliability of the operational criteria in the IHS Classification 1st edition were validated by clinical evaluations.8)9)

Several commentaries on the ICHD-2 have been published.2)5)10)-12)

Due to clinical necessity, an appendix for chronic migraine and medication overuse headache (MOH) were added in 2006.13)14) Furthermore, revision of the diagnostic criteria for secondary headache was proposed.15)16) The Classification Committee of the International Headache Society has been preparing for the publication of the third edition of ICHD. The ICHD Third Edition (beta version) (ICHD-3beta) was published in 2013.17)

Comments and Evidence

Headache classification according to the ICHD-3beta17)

The ICHD-3beta is composed of the following three parts

Part one The primary headaches: 4 types (57 subtypes)

Part two The secondary headaches: 8 types (117 subtypes)

Part three Painful cranial neuropathies, other facial pains and other headaches: 2 types (29 subtypes) supplement (17 subtypes)

Appendix (40 subtypes)

Broad Classification of Headache

• Part one: The primary headaches

1. Migraine

2. Tension-type headache (TTH)

3. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs)

4. Other primary headache disorders

• Part two: The secondary headaches

5. Headache attributed to trauma or injury to the head and/or neck

6. Headache attributed to cranial or cervical vascular disorder

7. Headache attributed to non-vascular intracranial disorder

8. Headache attributed to a substance or its withdrawal

9. Headache attributed to infection

10. Headache attributed to disorder of homoeostasis

11. Headache or facial pain attributed to disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth or other facial or cranial structure

12. Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder

• Part three: Painful cranial neuropathies, other facial and other headaches

13. Painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pains

14. Other headache disorders

• Appendix

Notes

• While the 1st edition had 13 categories, the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-2) has an added category “12. Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder” and thus a total of 14 categories.

• The ICHD-2 is an indispensable reference for the treatment and diagnosis, research, and education of headache disorders.

• At least, physicians should acquire a good knowledge of migraine (migraine without aura and migraine with aura), tension-type headache, cluster headache, and medication overuse migraine.

• Although the classification was revised by consolidating a vast volume of evidence on headache accumulated during 15 years since publication of the 1st edition, the basic policy is based on that of the 1st edition.

• Headache is classified based on the hierarchical classification system into group → type → subtype → sub-form. According to this system, each headache is coded in four digits. However, in clinical practice, classification up to two digits is sufficient.

• The following new headache disorders have been added: 1.5.1 Chronic migraine, 4.5 Hypnic headache, 4.6 Primary thunderclap headache, and 4.7 Hemicrania continua.

• For some headaches, the classification code was changed (for example; 1.3 Ophthalmoplegic migraine was moved to 13.17 Ophthalmoplegic migraine).

• Reflecting new concept of pathophysiology, the names of some headaches were changed [for example; trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias (TAC)].

• In the Japanese translation of the ICHD-2, some translated terms were revised, such as “Migraine not associated with aura” to “Migraine without aura”.

• This classification is compiled in the same format as the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Disease, and is compatible with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision: Neurological Adaptation (ICD-10NA).

• Soon after the publication of ICHD-2, the necessity to revise the diagnostic criteria for MOH was pointed out, and they were revised in March 2004. The major changes were (1) deletion of the characteristics of headache described in the subform of medication overuse headache; (2) addition of a new subform “8.2.6 Medication overuse headache attributed to combination of acute medications”. These two changes have been incorporated in the Japanese edition of the ICHD-2.2)18)

• The Japanese edition of ICHD-2 was published in 2004 in the official journal of the Japanese Headache Society.2) A book has since been published which detailed the errata of typographical errors and subsequent changes.19)

• An important point of the 2006 revision is that MOH can be diagnosed when there is misuse of medication, and the condition of headache improvement after drug discontinuation is no longer needed. For chronic migraine, while it was required in the past that the headache fulfills at least the diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura, at present it is not necessary that the headache shows the characteristics of migraine.16)

• The current diagnostic criterion D for secondary headaches is “Headache is greatly reduced or resolved within 3 months (this may be shorter for some disorders) after successful treatment or spontaneous remission of the causative disorder”. According to this, the headache should disappear completely or improve markedly after the causative disease is cured. However, some causative diseases cannot be cured and as a result headache is perpetuated. In the draft revision for ICHD-3, the diagnostic criterion C is revised substantially to better demonstrate the evidence of causal relationship. Fulfilment of at least two of five sub-criteria is required. In other words, while the current criterion C focuses only on the temporal relation of the development of headache with the onset of causative disorder, the new proposal has additional items: (C1) headache has developed in temporal relation to the onset of the causative disorder; (C2) headache has worsened in parallel with the causative disorder; (C3) headache has improved in parallel with the presumed causative disorder; (C4) headache has characteristics typical for the causative disorder; (C5) other evidence exists of causation. Moreover, for criterion D, while the current required evidence is resolution or greatly reduced of headache by cure of the causative disorder, the new proposal abolishes this and added “not better accounted for by other diagnosis”.15)16)

• The Japanese edition of ICHD-3beta was published in 2014.20)

Major References

• Commentaries on International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-2)2)5)10)-12)

• Original ICHD-3beta (in English). URL; http://www.ihs-classification.org/_downloads/mixed/International-Headache-Classification-III-ICHD-III-2013-Beta.pdf#search=%27ICHD3%27

• References

1) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1): 9-160.

2) The Headache Classification Committee of International Headache Society: International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II). Japanese Journal of Headache 2004; 31(1): 13-188. (In Japanese)

3) Isler H: Headache classification prior to the Ad Hoc criteria. Cephalalgia 1993 ; 13(Suppl 12): 9-10.

4) Manaka N: History of headache research. Advances in Neurological Sciences 2002; 46(3): 331-340. (In Japanese)

5) Gladstone JP, Dodick DW: From hemicrania lunaris to hemicrania continua: an overview of the revised International Classification of Headache Disorders. Headache 2004; 44(7): 692-705.

6) The Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache: Classification of Headache. Arch Neurol 1962; 6: 173-176.

7) Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society: Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8(Suppl 7): 1-96.

8) Granella F, D’Alessandro R, Manzoni GC, Cerbo R, Colucci D’Amato C, Pini LA, et al : International Headache Society classification: interobserver reliability in the diagnosis of primary headaches. Cephalalgia 1994; 14(1): 16-20.

9) Leone M, Filippini G, D’Amico D, Farinotti M, Bussone G: Assessment of International Headache Society diagnostic criteria: a reliability study. Cephalalgia 1994; 14(4): 280-284.

10) Sakai F: [Latest topic on headache] New international classification. No To Shinkei 2004; 56(8): 639-643. (In Japanese)

11) Fujiki N: [Cutting edge of headache care, for better headache care] New international diagnostic criteria for headache. Current Therapy 2004; 22(10): 979-982. (In Japanese)

12) Sakai F (ed.), Manaka S: International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II): Primary headaches, secondary headaches. ABC of New Diagnosis and Treatment (21) Neurology 2: Headache 2004: 9-15. (In Japanese)

13) Headache Classification Committee, Olesen J, Bousser MG, Diener HC, et al: New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2006; 26(6): 742-746.

14) Takeshima T, Manaka S, Igarashi H, Hirata K, Sakai F, International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society: On the addition of appendix for chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Japanese Journal of Headache 2007; 34(2): 192-193. (In Japanese)

15) Olesen J, Steiner T, Bousser MG, Diener HC, Dodick D, First MB, Goadsby PJ, Gobel H, Lainez MJ, Lipton RB, Nappi G, Sakai F, Schoenen J, Silberstein SD: Proposals for new standardized general diagnostic criteria for the secondary headaches. Cephalalgia 2009; 29(12): 1331-1336.

16) Takeshima T, Manaka S, Igashira H, Hirata K, Yamane K, Sakai F, New International Headache Classification and Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society: On the proposed revision of the diagnostic criteria for secondary headaches of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition/(ICHD-II). Japanese Journal of Headache 2010; 36(3): 235-238. (In Japanese)

17) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33(9): 629-808.

18) Igashira H, Manaka S: Revised diagnostic criteria for “8.2 Medication overuse headache” in the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition first revision (ICHD-II R1) — Difference from the Japanese Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition. Japanese Journal of Headache 2006; 33(1): 26-29. (In Japanese)

19) The Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (author), International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society (translator): Japanese Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition. Igakushoin, 2007. (In Japanese)

20) The Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (author), International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society (translator): Japanese Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (beta version). Igakushoin, 2014. (In Japanese)

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: Ichushi Web for articles published in Japan (2012/5/28)

classification of headache 58

headache classfication 118 (headache/TH or headache/AL) and (classification/TH or classification/AL) 798

• Search database: PubMed (2012/5/28)

classification of headache 3085

international classification of headache 1030

headache disorders/*classification 889

• Database used: Ichushi Web for articles published in Japan (2012/5/28)

(headache /TH or headache /AL) and diagnostic criteria /AL 242

• Database used: PubMed (2012/5/28)

headache/diagnostic criteria 3107

headache/*classification/*diagnosis 449

CQ I-2

How are primary headaches and secondary headaches differentiated?

Recommendation

Secondary headache should be suspected for the following: (1) headache with sudden onset, (2) headache never experienced before, (3) headache different from the customary headache, (4) headache that has increased in frequency and intensity, (5) headache begins after age 50, (6) headache with neurological deficit, (7) headache in a patient with cancer or immunodeficiency, (8) headache in a patient with psychiatric symptoms, and (9) headache in a patient with fever, neck stiffness or meningeal irritation. Intensive investigations are required.

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

Secondary headaches are headaches that develop due to some disorders, intracranial or otherwise, that cause the headache. In the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition beta version (ICHD-3beta), the secondary headaches are coded under 5. “Headache attributed to trauma or injury to the head and/or neck”, 6. “Headache attributed to cranial or cervical vascular disorder”, 7. “Headache attributed to non-vascular intracranial disorder”, 8. “Headache attributed to a substance or its withdrawal”, 9. “Headache attributed to infection”, 10. “Headache attributed to disorder of homoeostasis”, 11. “Headache or facial pain attributed to disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth or other facial or cranial structures”, and 12. “Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder”, and further subdivided into subtypes.1)2) There was an issue in the International Classification of Headache Disorders Second Edition regarding the classification and diagnosis of secondary headaches; which is, secondary headache cannot be diagnosed definitively if headache does not resolve after treatment.5) To address this issue, novel general diagnostic criteria for secondary headaches were proposed as a part of the revision task towards the publication of ICHD-3beta. As a result revision was adopted in ICHD-3beta.

Diverse disorders can cause secondary headaches, and some could be life-threatening. Therefore, careful examination is required. The phrase “Primary or secondary headache or both” is repeatedly discussed throughout the ICHD-3beta.1)2) The most important point in clinical care is that among the large number of disorders that may cause secondary headaches, do not miss the “headache for which a misdiagnosis will threaten life”.

Comments and Evidence

The diagnostic criterion D of ICHD-2 for secondary headaches states “Headache is greatly reduced or resolves within 3 months (this may be shorter for some disorders) after successful treatment or spontaneous remission of the causative disorder”. 5) According to this criterion, a diagnosis requires that the headache disappears completely or improves markedly after the causative disease is cured. However, some causative diseases cannot be cured, and as a result headache may be perpetuated. To address this issue, general diagnostic criteria for secondary headaches are proposed in ICHD-3beta,3)4) and they are presented below.

A. Any headache fulfilling criterion C

B. Another disorder scientifically documented to be able to cause headache has been diagnosed

C. Evidence of causation demonstrated by at least two of the following:

1. headache has developed in temporal relation to the onset of the presumed causative disorder

2. one or both of the following:

a) headache has significantly worsened in parallel with worsening of the presumed causative disorder

b) headache has significantly improved in parallel with improvement of the presumed causative disorder

3. headache has characteristics typical for the causative disorder

4. other evidence exists of causation

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Currently, the diagnostic criteria for each of the secondary headaches are being revised in line with the above general criteria.

First of all, differentiation between the primary headaches and the secondary headaches is important. The features that lead to a suspicion of secondary headache include “headache with sudden onset”, “headache never experienced before”, “headache different from the customary headache”, and “headache that tends to worsen”. The probability of secondary headache has to be considered for headaches that begin after age 50; headaches associated with neurological symptoms such as paralysis or abnormal visual acuity or visual field, change in consciousness level, and seizure; headaches associated with fever, rash, or neck stiffness; and headaches with a history of systemic disease.6) In clinical interview, the question “Have you experienced the same headache before?” is very useful. If the headache has never been experienced before or is the worst headache ever experienced in life, then it is important to conduct neurological examinations and evaluations, and select appropriate imaging studies, blood tests and cerebrospinal fluid test.7) Start treatment if the test and examination results exclude secondary headaches with high emergency, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, and do not contradict with a diagnosis of primary headache. If the clinical course is not typical of primary headache or if response to treatment is poor, reconsider the possibility of secondary headache.8) Especially, in a patient with primary headache who becomes affected by a disease that causes secondary headache, careful examination is needed so as not to delay the diagnosis.

Secondary headache has to be suspected and imaging studies are required in children with headaches that do not respond to drugs within 6 months; headaches associated with papilloedema, nystagmus, or gait/motor disorder; headaches with no family history of migraine; headaches associated with impaired consciousness or nausea; recurring headaches during sleep causing wakening; and headaches with a family history or medical history of central nervous system disease.9)

Although history taking and physical/neurological examinations are important for the differentiation between primary and secondary headaches, the significance of diagnostic imaging has also been pointed out.10) According to the study of Mayer et al.,11) 54 of 217 patients (25%) who had subarachnoid hemorrhage were misdiagnosed. The misdiagnoses included meningitis (15%), migraine (13%), headache of unknown etiology (13%), cerebral infarction (9%), headache attributed to arterial hypertension (7%), and tension-type headache (7%). Cautions in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage are described in a separate CQ (CQ 1-3, page 8), and will not be discussed here.

• References

1) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33(9): 629-808.

2) The Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (author), International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society (translator): Japanese Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (beta version). Igakushoin, 2014. (In Japanese)

3) Olesen J, Steiner T, Bousser MG, Diener HC, Dodick D, First MB, Goadsby PJ, Gobel H, Lainez MJ, Lipton RB, Nappi G, Sakai F, Schoenen J, Silberstein SD: Proposals for new standardized general diagnostic criteria for the secondary headaches. Cephalalgia 2009; 29(12): 1331-1336.

4) Takeshima T, Manaka S, Igarashi H, Hirata K, Yamane K, Sakai F: International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society: On the proposed revision of the diagnostic criteria for secondary headaches in the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II). Japanese Journal of Headache 2010; 36(3): 235-238. (In Japanese)

5) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1): 9-160.

6) Evans RW: Diagnostic testing for migraine and other primary headaches. Neurol Clin 2009; 27(2): 393-415.

7) Takeshima T, Kanki R, Yamashita S: The know-how to diagnose secondary headaches. Chiryo 2011; 93(7): 1544-1549. (In Japanese)

8) Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dalessio DJ: Overview, Diagnosis and Classification of headache. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dalessio DJ (eds): Wolff’s Headache and other Head Pain 7th ed, pp6-26, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001.

9) Medina LS, D’Souza B, Vasconcellos E: Adults and children with headache: evidence-based diagnostic evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2003; 13(2): 225-235.

10) Aygun D, Bildik F: Clinical warning criteria in evaluation by computed tomography the secondary neurological headaches in adults. Eur J Neurol 2003; 10(4): 437-442.

11) Mayer PL, Awad IA, Todor R, Harbaugh K, Varnavas G, Lansen TA, Dickey P, Harbaugh R, Hopkins LN: Misdiagnosis of symptomatic cerebral aneurysm. Prevalence and correlation with outcome at four institutions. Stroke 1996; 27(9): 1558-1563.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: Pub Med (2012/4/30)

{secondary headache} & {diagnosis} 2351

• Search database: Ichushi for articles published in Japanese (2012/4/30)

{secondary headache} & {diagnosis}212

• One reference added by manual search (reference 7)

CQ I-3

How is subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosed?

Recommendation

• When subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected, a rapid and precise diagnosis and treatment by specialist are necessary.

• The typical symptom is “sudden excruciating headache never experienced before”.

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage may manifest warning symptoms from mild bleeding. Pay attention when there is abrupt onset of headache accompanied by nausea or vomiting, dizziness, diplopia or impaired vision, and delirium.

• Regarding neuroimaging, early-stage CT or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MR imaging has high diagnostic value.

• When subarachnoid hemorrhage is strongly suspected, a lumbar puncture should be considered even when neuroimaging is negative.

• Several days following the onset of headache, cerebral ischemic symptoms may appear due to cerebral vasoconstriction.

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

Subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by a ruptured cerebral aneurysm has poor outcome. Since misdiagnosis or delay in diagnosis may worsen the outcome, the objective of this section is to improve the capability of the primary care physician to differentiate subarachnoid hemorrhage from other conditions.

In this section, the diagnostic criteria in the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition beta version (ICHD-3beta) are provided, and updated knowledge is added.

Comments and Evidence

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage have been published in Japan and overseas.1)2) The prognosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage is poor; overall mortality of 25-53% has been reported.3)4) The most important factor that aggravates the prognosis is rebleeding from the ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Since rebleeding is a common cause of misdiagnosis and delay in diagnosis, an accurate diagnosis together with treatment provided by specialist are essential.5)6) Before the onset of the major attack of subarachnoid hemorrhage accompanied by “abrupt onset of the worst headache ever experienced”,3) minor leak occurs in around 20% of the patients. Misdiagnosis of these warning leaks would deteriorate the outcome; therefore attention has to be given to these cases.7)8) The most common symptom of minor leak is sudden headache, but may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting, dizziness, delirium,9) oculomotor paralysis, and visual disturbance.10) Careful history taking is essential. The common neck stiffness is not observed during the very early stage of subarachnoid hemorrhage, therefore be aware that “absence of neck stiffness does not exclude a diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage”. CT is a useful neuroimaging modality. The diagnostic power increases by comparing with former images.11)12) The diagnostic rate is 98-100% when performed within 12 hours of onset.13)-15) When a CT scan shows no abnormality, FLAIR MR imaging is useful.8)16)-18) Even when imaging findings are negative, a lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid examination is important, especially at 12 hours or later after onset.1)2)4)13)19)

• For Reference

According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition beta version (ICHD-3beta) published in 2013, the diagnostic criteria for 6.2.2 Headache attributed to non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage are as follows16):

A. Any new headache fulfilling criterion C

B. Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in the absence of head trauma has been diagnosed

C. Evidence of causation demonstrated by at least two of the following:

1. headache has developed in close temporal relation to other symptoms and/or clinical signs of SAH, or has led to the diagnosis of SAH

2. headache has significantly improved in parallel with stabilization or improvement of other symptoms or clinical or radiological signs of SAH

3. headache has sudden or thunderclap onset

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

• References

1) Yoshimine T (Ed.): Evidence-based guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, the second edition. Surg Cereb Stroke 2008; 36(Suppl I): 1-80. (In Japanese)

2) Bederson JB, Connolly ES Jr, Batjer HH, Dacey RG, Dion JE, Diringer MN, Duldner JE Jr, Harbaugh RE, Patel AB, Rosenwasser RH; American Heart Association: Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 2009; 40(3): 994-1025.

3) Talavera JO, Wacher NH, Laredo F, Halabe J, Rosales V, Madrazo I, Lifshitz A: Predictive value of signs and symptoms in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage among stroke patients. Arch Med Res 1996; 27(3): 353-357.

4) van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ: Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 2007; 369(9558): 306-318.

5) Kassell NF, Torner JC, Haley EC Jr, Jane JA, Adams HP, Kongable GL: The International Cooperative Study on the Timing of Aneurysm Surgery. Part 1: Overall management results. J Neurosurg 1990; 73(1): 18-36.

6) Inagawa T: Delayed diagnosis of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients: a community-based study. J Neurosurg 2011; 115(4): 707-714.

7) Bassi P, Bandera R, Loiero M, Tognoni G, Mangoni A: Warning signs in subarachnoid hemorrhage: a cooperative study. Acta Neurol Scand 1991; 84(4): 277-281.

8) Jakobsson KE, Saveland H, Hillman J, Edner G, Zygmunt S, Brandt L, Pellettieri L: Warning leak and management outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1996; 85(6): 995-999.

9) Caeiro L, Menger C, Ferro JM, Albuquerque R, Figueira ML: Delirium in acute subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 19(1): 31-38.

10) McCarron MO, Alberts MJ, McCarron P: A systematic review of Terson’s syndrome: frequency and prognosis after subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75(3): 491-493.

11) Johansson I, Bolander HG, Kourtopoulos H: CT showing early ventricular dilatation after subarachnoidal hemorrhage. Acta Radiol 1992; 33(4): 333-337.

12) van der Wee N, Rinkel GJ, Hasan D, van Gijn J: Detection of subarachnoid haemorrhage on early CT: is lumbar puncture still needed after a negative scan? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 58(3): 357-359.

13) Liebenberg WA, Worth R, Firth GB, Olney J, Norris JS: Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: guidance in making the correct diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81(957): 470-473.

14) Given CA 2nd, Burdette JH, Elster AD, Williams DW 3rd: Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential imaging pitfall associated with diffuse cerebral edema. Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24(2): 254-256.

15) Boesiger BM, Shiber JR: Subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosis by computed tomography and lumbar puncture: are fifth generation CT scanners better at identifying subarachnoid hemorrhage? J Emerg Med 2005; 29(1): 23-27.

16) The Headache Classification Committee of International Headache Society: International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition beta version 2013. Cephalalgia 33 (9): 696-697.

17) Leblanc R: The minor leak preceding subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1987; 66(1): 35-39.

18) Mitchell P, Wilkinson ID, Hoggard N, Paley MN, Jellinek DA, Powell T, Romanowski C, Hodgson T, Griffiths PD: Detection of subarachnoid haemorrhage with magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70(2): 205-211.

19) Wood MJ, Dimeski G, Nowitzke AM: CSF spectrophotometry in the diagnosis and exclusion of spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci 2005; 12(2): 142-146.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2011/10/15)

Subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosis

& human

& English/Japanese

& 2005-

& practical guideline/review = 457 articles

Cerebral aneurysm

& Subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosis

& human & English/Japanese & 2005-

& RCT/metaanalysis = 51 articles

CQ I-4

What are the procedures for managing headache in the emergency room?

Recommendation

For patients presenting with a major complaint of headache, differentiation between primary headache and secondary headache is the most important. First screening for life-threatening headaches should be performed, with special attention to headache due to subarachnoid hemorrhage. History taking, physical and neurological examination, and neuroimaging (CT/MRI) are important for a diagnosis of headache. Even when neuroimaging shows no abnormality, lumbar puncture should be considered if subarachnoid hemorrhage is strongly suspected.

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

Patients with diverse complaints of headaches visit the emergency room, ranging from highly emergent subarachnoid hemorrhage to primary headaches. According to the data (between January 1997 and December 1999) of the emergency outpatient department of Keio University Hospital, headache emergencies occupied 3.2% of all emergency cases, 38.3% of which were primary headaches (including migraine 6.6%) and 53.6% were secondary headaches, with subarachnoid haemorrhage constituting 8.1%.1) In an emergency department of a hospital in the United States, the vast majority of patients who presented with acute primary headache had migraine (95%).2) However, the emergency department physicians diagnosed migraine in only 32% of the patients, and only 7% of the patients received medications specific for migraine. Emergency physicians are required to have the competency to diagnose secondary headaches, and the knowledge to diagnose and treat primary headaches.

Comment and Evidence

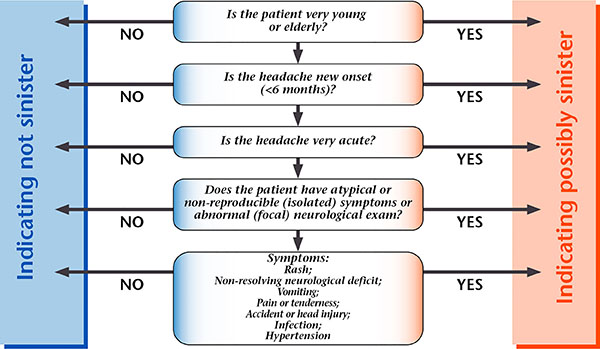

First, physicians should know about headache classification as described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II).3)4) A sinister headache should be suspected if the onset and clinical course fulfill the following criteria5): patient is younger than 5 years or older than 50 years; new onset headache within the past 6 months; very acute course reaching the highest intensity within 5 minutes; atypical symptoms, headache accompanied by symptoms never before experienced; presence of local neurological abnormalities; non-resolving neurological symptoms; presence of rash, head tenderness, head injury, infection, and hypertension.

Dodick6) proposed concise and easy to understand clinical clues for the differentiation between primary and secondary headaches, abbreviated as SNOOP.

SNOOP: Clinical clues for clinical diagnosis

Systemic symptoms/signs (fever, myalgias, weight loss)

Systemic disease (malignancy, acquired immune deficiency syndrome)

Neurologic symptoms or signs

Onset sudden (thunderclap headache)

Onset after age 40 years

Pattern change (progressive headache with loss of headache-free periods, change in type of headache)

In a study connected on 264 patients visiting an internal medicine department with a complaint of headache but no neurological abnormalities, patients were asked three questions: Q1 “Is your headache the worst ever? (worst)”, Q2 “Is your headache getting worse? (worsening)”, and Q3 “Was the onset of headache sudden? (sudden)”.7) Among the three questions, Q2 (worsening) had the highest positive predictive value, followed by Q1 (worst). It is noteworthy that none of the patients who were negative for all three questions had red flag headaches.

Cortelli et al.8) proposed evidence-based diagnosis of non-traumatic headache in the emergency department (ER). They summarized the consensus regarding four clinical scenarios based on extensive literature review.

Scenarios for the diagnosis of non-traumatic acute headache

• Scenario 1

Adult patients admitted to ER for severe headache (“worst headache”)

* with acute onset ( “thunderclap headache”)

* with focal neurological findings (or non-focal, such as decreased level of consciousness)

* with vomiting or syncope at onset of headache

→ Perform head CT

→ If CT scan is negative or uncertain, or of poor quality, perform lumbar puncture

→ If lumbar puncture shows no abnormality, evaluation by a neurologist within 24 hours is necessary

•Scenario 2

Adult patients admitted to ER for severe headache

* With fever and/or neck stiffness

→ Perform head CT and lumbar puncture

• Scenario 3

Adult patients admitted to ER for the following conditions:

* headache of recent onset (days or weeks)

* progressively worsening headache, or persistent headache

→ Perform head CT

→ Perform routine blood tests (including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein)

→ If tests are negative, perform neurological evaluation within 7 days

• Scenario 4

Adults with a past history of headache

* Headache similar to previous headache in intensity, duration and associated symptoms

→ Perform vital signs examination, neurological evaluation and routine blood tests

→ If tests are negative, discharge patient from ER

→ After discharge, provide collaborated care

Although the medical care environment in Japan differs in some aspect from other countries, the above diagnostic scenarios provide useful references. When MRI is used as the first neuroimaging method for acute headache, FLAIR or T2-weighted imaging is essential.

Kowalski et al.9) conducted a cohort study on 482 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage admitted to a tertiary hospital, to analyze the association of initial misdiagnosis with outcome. According to their study, 12% of the patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage were misdiagnosed, and migraine or tension-type headache (36%) was the most common incorrect diagnosis. Misdiagnosis was common in patients with mild bleeding or normal mental status. Misdiagnosis was associated with poor survival and functional outcome. More aggressive CT scanning in patients suspected of subarachnoid haemorrhage, even though the symptoms are mild, may reduce the frequency of misdiagnosis. Even when CT and cerebrospinal fluid test are negative, conducting FLAIR MRI may lead to a diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage.10)

Lewis and Qureshi11) analyzed the cause of acute headache in children and adolescents (boys and girls). Their results showed that upper respiratory tract infection with fever, sinusitis, and migraine were the most common causes. Physicians have to pay special attention if the acute headache is located in the occipital region or if the patient is unable to describe the quality of the pain. Serious underlying diseases such as brain tumor and intracranial hemorrhage are rare; when present, they are accompanied by multiple neurological signs (such as ataxia, hemiparesis, and papilledema).

• References

1) Yokoyama M, Hori S, Aoki K, Fujishima S, Kimura Y, Suzuki M, Aikawa N: Headache in patients transported to emergency department. Japanese Journal of Headache 2001; 28(1): 4-5. (In Japanese)

2) Blumenthal HJ, Weisz MA, Kelly KM, Mayer RL, Blonsky J: Treatment of primary headache in the emergency department. Headache 2003; 44(10): 1026-1031.

3) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1): 9-160.

4) The Headache Classification Committee of International Headache Society: International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II). Japanese Journal of Headache 2004; 31(1): 13-188. (In Japanese)

5) Dowson AJ, Sender J, Lipscombe S, Cady RK, Tepper SJ, Smith R, Smith TR, Taylor FR, Boudreau GP, van Duijn NP, Poole AC, Baos V, Wober C: Establishing principles for migraine management in primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2003; 57(6): 493-507.

6) Dodick DW: Clinical clues (primary/secondary), The 14th Migraine Trust International Symposium. London, 2002.

7) Basugi M, Ikusaka M, Mikasa G, Kim S: Usefulness of three simple questions to detect red flag headaches in outpatient settings. Japanese Journal of Headache 2006; 33(1): 30-33.

8) Cortelli P, Cevoli S, Nonino F, Baronciani D, Magrini N, Re G, De Berti G, Manzoni GC, Querzani P, Vandelli A; Multi-disciplinary Group for Nontraumatic headache in the Emergency Department: Evidence-based diagnosis of nontraumatic headache in the emergency department: a consensus statement on four clinical scenarios. Headache 2004; 44(6): 587-595.

9) Kowalski RG, Claassen J, Kreiter KT, Bates JE, Ostapkovich ND, Connolly ES, Mayer SA: Initial misdiagnosis and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. JAMA 2004; 291(7): 866-869.

10) Ogami R, Igawa F, Ohbayashi N, Imada Y, Hidaka T, Inagawa T: A case of subacute subarachnoid hemorrhage not diagnosed by cerebrospinal fluid examination: usefulness of emergent MRI. Neurological Surgery 2003; 31(6): 663-668. (In Japanese)

11) Lewis DW, Qureshi F: Acute headache in children and adolescents presenting to the emergency department. Headache 2000; 40(3): 200-203.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2012/5/5)

No. Request & Records

1 Headache 55659

2 emergency 210382

3 #1 & #2 1907

4 etiology 6577149

5 management 1654390

6 diagnosis 7723671

7 therapy 6548922

8 treatment 7421136

9 “differential diagnosis” 391173

10 #3 & #4 1076

11 #3 & #5 704

12 #3 & #6 1405

14 #3 & #8 1324

15 #3 & #9 289

16 #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 1829

17 “Evidence-Based-Medicine”/all subheadings 49397

18 guidelines 219788

19 consensus 96334

20 #16 & #17 11824

21 #16 & #18 8

22 #16 & #19 2 23 #20 or #21 or #22 11

• Search database: Ichushi for articles published in Japan (2012/5/5)

(headache) & (emergency) 1103

CQ I-5

How should primary care physicians manage headache?

Recommendation

Primary care physicians should bear in mind to differentiate between primary headaches and secondary headaches, and in case of difficulties with diagnosis, should promptly refer the patient to a specialist. For primary headaches, primary care physicians should be able to correctly diagnose and treat especially migraine and tension-type headache.

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

Headache is one of the common complaints encountered in routine clinical care. It is estimated that primary care physicians accurately diagnose headache at a rate of approximately 50%. The issue for primary care physicians is how to improve the precision of diagnosis and treatment of headache. When providing headache care, primary care physicians should first of all diagnose the cause of headache accurately. To do this requires knowledge regarding the classification of headaches. When primary care physicians with no access to head CT and MRI encounter difficulties in differentiating secondary headaches from primary headaches, they should refer the patient to a specialist as soon as possible. Especially in the case of sudden onset of headache in which subarachnoid hemorrhage cannot be excluded, the patient should be referred to a neurosurgeon.

Although primary headaches are considered not to cause residual organic damage to the brain, headache attacks cause disability in daily life. Therefore, appropriate treatment is required to improve the daily life of the patients.

For clinical care of headache, use simple screeners and headache diary for diagnosis, severity evaluation, and treatment; evaluate the treatment effect appropriately; and it is also important to give proper guidance to the patients about the timing of taking acute medications for headache and on prophylactic treatment.

Comments and Evidence

First, primary care physicians should know about the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II) developed by the International Headache Society (IHS),1) which set out diagnostic criteria for each of the headache types. Furthermore, they should know that according to ICHD-II, headaches are classified into primary headaches and secondary headaches, and that primary headaches include migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache, while secondary headaches are caused by various neurological disorders and may include systemic diseases.1) When primary care physicians provide care for headache, it is important that first of all they have knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for primary headaches. Although ICHD-II classifies in a hierarchical manner, primary care physicians should be familiar with at least the first level (for example, the level to diagnose “migraine”). To diagnose primary headaches, it is necessary to exclude the possibility of secondary headaches. In practice, precise history taking, neurological evaluation, sometimes blood tests and neuroimaging are necessary to exclude secondary headaches. If eye disease or disease of other discipline is suspected from the beginning, refer the patient to the respective specialist as soon as possible. When a diagnosis of primary headache is established, plan treatment according to this guideline.

Simple screeners headache for use by primary care physicians have been developed, and reported to have high specificity for the diagnosis of migraine.2)3) One of them consists of questions on the frequency of headache, and the use of medications.2) Another screener contains questions based on the diagnostic criteria of ICHD-II, including the frequency and duration of headache, aura, and degree of disability.3) MIDAS and HIT-6 are tools that evaluate objectively the impact of headache on patient’s activities of daily living. Use these screeners to aid diagnosis and evaluation of severity, and provide treatment appropriate to individual patients. Use headache diary for follow-up observation. Advise patients on the timing of taking medications for migraine. Provide rescue treatment when the early treatment fails. Offer prophylactic treatment when headache occurs frequently. As such, primary care physicians also have to be engaged in many aspects of headache management.4)5)

• References

1) The Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (author), International Headache Classification Promotion Committee of Japanese Headache Society (translator): Japanese Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition. Igakushoin, 2007. (In Japanese)

2) Maizels M, Burchette R: Rapid and sensitive paradigm for screening patients with headache in primary care settings. Headache 2003; 43(5): 441-450.

3) Cousins G, Hijazze S, Van de Laar FA, Fahey T: Diagnostic accuracy of the ID Migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache 2011; 51(7): 1140-1148.

4) Dowson AJ, Sender J, Lipscombe S, Cady RK, Tepper SJ, Smith R, Smith TR, Taylor FR, Boudreau GP, van Duijin NP, Poole AC, Baos V, Wober C: Establishing principles for migraine management in primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2003; 57(6): 493-507.

5) Dowson AJ, Lipscombe S, Sender J, Rees T, Watson D; MIPCA Migraine Guidelines Development Group: Migraine in primary care: New guidelines for the management of migraine in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin 2002; 18(7): 414-439.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2011/12/21)

Headache & ‘primary care’ 1078

Headache & ‘primary care’ & diagnosis 710

Headache & general practitioner 326

Headache & general practitioner & diagnosis 190

Headache & algorithms 171

Headache & screener 15

CQ I-6

How should dentists manage headache?

Recommendation

• Dentists should differentiate between headache and temporomandibular disorder.

• In the differential diagnosis of toothache of unknown cause, the possibility of the involvement of the teeth by primary headaches and secondary headaches has to be considered.

• Cases with concurrent headache which are difficult to diagnose should be referred promptly to specialists.

| Grade B |

Background and Objective

Temporomandibular disorder occurs overwhelmingly more often in women, and is known to be a disease with gender difference. Primary headaches, especially migraine and tension-type headache, tend to occur concurrently with temporomandibular disorder. Moreover, since the pain experienced by patients with cluster headache and migraine sometimes involves the face and the teeth, these patients may visit dentists with the major complaint of toothache or temporomandibular pain. Dentists are recommended to have the capability of differentiating these headaches from temporomandibular disorder and odontogenic pain.

On the other hand, it has been reported that dental disease may be a cause of secondary headaches.

Comments and Evidence

In the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (beta version) (ICHD-3beta) of the International Headache Society (IHS),1) tension-type headache is subdivided into infrequent episodic tension-type headache, frequent episodic tension-type headache, and chronic tension-type headache; and each further subdivided into two subforms: with and without pericranial tenderness. Increased pericranial tenderness induced by palpation is the most significant abnormal finding in patients with tension-type headache. The tenderness increases with the intensity and frequency of headache, and is further increased during actual headache. Pericranial tenderness is in fact tenderness of the frontal muscle, temporal muscle, masseter muscle, lateral and medial pterygoid muscle, sternocleidomastoid muscle, splenius muscle, and trapezius muscle. In another words, tension-type headache and myogenic temporomandibular disorder may be regarded as similar diseases with the same source of pain but different pain reception sites. Because the muscles are affected, stiff shoulders and stiff neck often occur concurently.2)3)

In addition, studies have shown a pathological association between temporomandibular disorder and headache, and between toothache and headache.4)5)

Migraine is a disease with high prevalence, and therefore may coexist incidentally with other diseases that have high prevalence. A report has indicated that one-half of the patients with temporomandibular disorder have migraine concurrently. Patients with migraine sometimes manifest allodynia in the crainocervical region both during headache and when in remission, probably a result of lowered threshold of pericranial tenderness.6) Furthermore, the pain in migraine not only involves the first division of the trigeminal nerve, but also the second and third divisions, and may sometimes be misdiagnosed as temporomandibular disorder or toothache.7) This is a result of sensitization of the central nervous system due to headache attack, and conversely deep pain in the craniocervical region may also sensitize the central nervous system. Consequently, temporomandibular disorder is a factor that contributes to aggravate headache frequency or induce chronicity of headache.4)5)

• References

1) Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33(9): 629-808.

2) Jensen R, Rasmussen BK, Pedersen B, Olesen J: Muscle tenderness and pressure pain thresholds in headache. A population study. Pain 1993; 52(2): 193-199.

3) Schmidt-Hansen PT, Svensson P, Bendtsen L, Graven-Nielsen T, Bach FW: Increased muscle pain sensitivity in patients with tension-type headache. Pain 2007 ; 129(1-2): 113-121.

4) Bevilaqua-Grossi D, Lipton R, Bigal ME: Temporomandibular disorders and migraine chronification. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2009; 13(41): 314-318.

5) Goncalves DA, Speciali JG, Jales LC, Camparis CM, Bigal ME: Temporomandibular symptoms, migraine, and chronic daily headaches in the population. Neurology 2009; 73(8): 645-646.

6) Bevilaqua-Grossi D, Lipton RB, Napchan U, Grosberg B, Ashina S, Bigal ME: Temporomandibular disorders and cutaneous allodynia are associated in individuals with migraine. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(4): 425-432.

7) Graff-Radford SB: Headache problems that can present as toothache. Dent Clin North Am 1991; 35(1): 155-170.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2011/12/21)

headache & dental pain 537

TMD & migraine headache 33

TMD & tension-type headache 38

CQ I-7

Are headache clinic and headache specialist necessary? Is collaborative care useful for primary headaches?

Recommendation

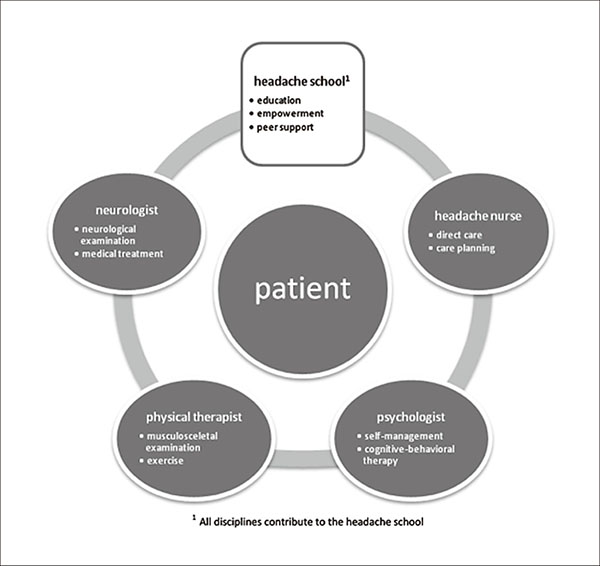

Headache clinic is necessary to improve the satisfaction and quality of life (QOL) of patients with chronic headache. In the headache clinic, diagnosis and treatment should be provided by headache specialists with expert knowledge not only in highly emergent secondary headaches but also in chronic headaches. Especially, when primary care physicians have difficulties with diagnosis or treatment of headache, referral to or consultation with headache specialists is recommended. Collaboration between primary care physicians and headache specialists for the management of primary headaches increases the satisfaction and QOL of patients. Collaborative care for primary headaches should be further promoted.

| Grade A |

Background and Objective

Many patients with chronic headaches have headaches that seriously interfere with their daily activities. Yet, the needs of the patients were not met. Many patients either never sought medical care or were not diagnosed and treated appropriately even if they had received medical care, while others were always anxious that as the doses of analgesics increased, the medications might become ineffective. To address this situation, the Japanese Headache Society started to certify headache specialists from 2005, and began to establish headache clinics nationwide. A nationwide epidemiological survey in Japan estimated that approximately 40 million persons were affected by chronic headache.1) The numbers of headache specialists and headache clinics remain insufficient.

Comment and Evidence

According to a nationwide epidemiological survey in Japan, the number of persons affected by headache was estimated to be approximately 40 million, 8.5 million of whom had migraine and 74% of whom had serious disability in daily living because of the headache.1) The economic loss because of headache, including direct loss due to medical expenses and indirect loss due to the incapability to work, amounts to nearly three hundred billion yen a year.2) The World Health Organization (WHO) ranked migraine at the 19th place among diseases that shorten the healthy lifespan.3) Approximately 70% of migraine patients never consult medical facilities, and approximately 50% are taking only over-the-counter medications.1)4) Most of the patients with chronic headache who have never consulted a medical facility, patients who have not been appropriately diagnosed, and patients who are treated only with over-the-counter medications have serious disability in daily living. In addition, even among those who have consulted medical facilities, many are not accurately diagnosed and do not receive appropriate treatment.5)6) In the background of such situation, issues on the medical facility side include the following: (1) only neuroimaging is conducted to exclude organic diseases, and the diagnosis for migraine is inadequate; (2) even when migraine is diagnosed, knowledge on treatment is inadequate leading to patient dissatisfaction; and (3) diagnosis and treatment are not explained adequately to patients. On the other hand, there are also issues on the patient’s side, including: (4) feel assured by exclusion of organic diseases alone, and do not ask for treatment; and (5) are embarrassed by consulting medical facilities because of headache, due to a lack of understanding that migraine is a condition that requires treatment.7) Through the establishment and publicity of headache clinics, the number of patients with chronic headache consulting headache specialists has increased.5)-9) When the headache clinic was opened at the Department of Neurology at Yamaguchi University, the event was publicized in the press and television, resulting in an increase of new headache patients by 7.4-fold, especially with a significant increase in patients with migraine.8) Among patients with migraine consulting the headache clinic, their primary purpose is to seek treatment, followed by to know the cause of their headache.7) In a study of 38 patients with migraine referred by primary care physicians to a specialist headache clinic in Singapore, the pain intensity, MIDAS score, and SF-36 score improved after three months, and patient satisfaction also increased.10) Referral from general physicians to headache specialists benefits the patients by ameliorating the fear toward headache, improving the headache per se, and improving QOL.11)12)

To improve headache care, experienced headache specialists and headache clinics staffed by headache specialists are essential.9) An accurate diagnosis of headache and every possible approach to relieve the disease burden of headache patients should be provided.

• References

1) Sakai F, Igarashi H: Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia 1997; 17(1): 15-22.

2) Sakai F: [Special Issue: Primary Care for Headache] Headache diagnosis system (headache specialist, headache clinic, medical collaboration). Chiryo 2011; 93(7): 1609-1613. (In Japanese)

3) World Health Organization: The World Health Report 2001-Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. http: //www.who.int/whr/2001/en/

4) Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, Ijiri T, Kusumi M, Wakutani Y, Mori M, Kawashima M, Kowa H, Adachi Y, Urakami K, Nakashima K: Population-based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: the Daisen study. Headache 2004; 44(1): 8-19.

5) Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Simon D: Medical consultation for migraine: results from the American Migraine Study. Headache 1998; 38(2): 87-96.

6) Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Liberman JN, Stewart WF: Patterns of health care utilization for migraine in England and in the United States. Neurology 2003; 60(3):441-448.

7) Tada Y, Negoro Y, Ogasawara J, Kawai M, Morimatsu M: A dramatic increase in the number of outpatients with migraine after the opening of a headache clinic. Yamaguchi Igaku 2003; 52(5): 169-173. (In Japanese)

8) Kakinuma S, Negoro K, Tada Y, Morimatsu H: Effects of mass media announcements on the number of outpatients visiting a headache clinic. Shinkei Iryo 2003; 20(1): 63-69. (In Japanese)

9) Sakai F (Ed.) Negoro Y, Tada Y: Headache clinic. Latest Medicine Supplement [ABC of New Diagnosis and Treatment 21/ Neurology 2 Headache 2004: 26-32. (In Japanese)

10) Soon YY, Siow HC, Tan CY: Assessment of migraineurs referred to a specialist headache clinic in Singapore: diagnosis, treatment strategies, outcomes, knowledge of migraine treatments and satisfaction. Cephalalgia 2005; 25(12): 1122-1132.

11) Bekkelund SI, Salvesen R; North Norway Headache Study (NNHS): Are headache patients who initiate their referral to a neurologist satisfied with the consultation? A population study of 927 patients — the North Norway Headache Study (NNHS). Fam Pract 2001; 18(5): 524-527.

12) Salvesen R, Bekkelund SI: Aspects of referral care for headache associated with improvement. Headache 2003; 43(7): 779-783.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2012/4/30)

{headache clinic} 3175

& ({role} OR {necessity}) 232

&specialist 62

(1) & {medical treatment} & {migraine} 73

• Search database: Ichushi Web for articles published in Japan (2012/4/30)

headache clinic 142

specialist headache clinic 12

headache center 28

headache specialist 7

• Secondary source: 4 references from manual search (references 1, 3, 4 and10)

CQ I-8

How are algorithms used?

Recommendation

The diagnosis and treatment of headache start from differentiating secondary headaches, especially the dangerous (life-threatening) headaches. Next, the primary headaches, including migraine, should be diagnosed. Simple diagnostic algorithms are a powerful tool that provides clues to the diagnosis of headaches in the clinical setting.

| Grade B |

Background and Objective

The objective of this section is to illustrate how algorithms can be used for effective diagnosis of headache in the busy routine clinical setting.

Comments and Evidence

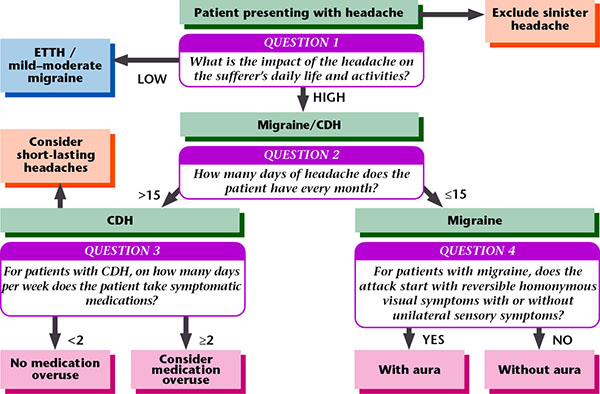

The diagnosis and treatment of headache start from excluding the secondary headaches that are dangerous headaches. An algorithm for use by primary care physicians is available (Figure 1). After screening for dangerous headaches, the diagnosis of chronic headaches that are primary headaches including migraine then begins.1)-4) The algorithm comprises four major questions: “What is the impact of the headache on daily life?”, “How many days of headache in a month?”, “how many days per week are medications taken?” and “Does the attack start with reversible homonymous visual symptoms or unilateral sensory symptoms?”2) (Figure 2).

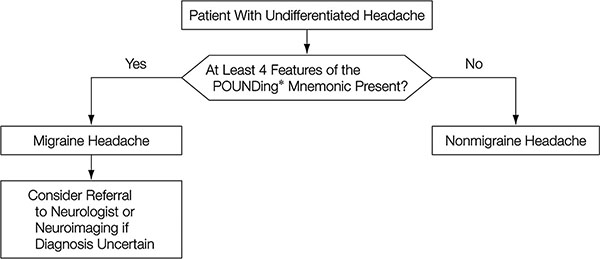

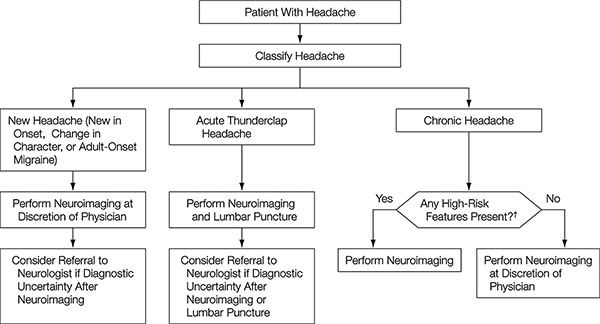

For migraines, “POUNDing” that is composed of the acronyms characterizing the five symptoms of migraine is useful.4) POUNDing stands for Pulsating, duration of 4-72 hOurs, Unilateral, Nausea, and Disabling. If four of the five are satisfied, then there is a high probability of migraine (Figure 3). Moreover, another algorithm examines the common clinical question of what kinds of patients require neuroimaging. Six items: “cluster-type headache”, “abnormal findings on neurologic examination”, “undefined headache (not cluster-, migraine-, or tension-type)”, “headache with aura”, “headache aggravated by exertion or valsalva-like maneuver”, and “headache with vomiting”, are useful in judging whether neuroimaging is necessary (Figure 4). An algorithm for differentiating chronic daily headaches5) and another algorithm for the management of primary headaches in the emergency setting6) have also been reported.

Sinister Headache Algorithm @2004 www.pico.org.uk

Figure 1. Simple diagnostic algorithm for screening sinister headache.

Reproduced with permission from Migraine Action.

GP Diagnostic Algorithm @2004 www.pico.org.uk

Figure 2. Algorithm for screening headache.

Reproduced with permission from Migraine Action.

Figure 3. Algorithm for the approach to headache: Does this patient have a migraine headache?

*POUNDing: Pulsatile; duration 4-72 hOurs; Unilateral; Nausea; Disabling

[Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, Tomlinson GA, McCrory DC, Booth CM: Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA 2006;296(10):1274-1283. Copyright © (2006) American Medical Association. All rights reserved.]

Figure 4. Algorithm for the approach to headache: Does this patient need neuroimaging?

†Cluster-type headache, abnormal findings on neurologic examination, undefined headache (not cluster-, migraine-, or tension-type), headache with aura, headache aggravated by exertion or valsalva-like maneuver, headache with vomiting

[Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, Tomlinson GA, McCrory DC, Booth CM: Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA 2006;296(10):1274-1283. Copyright © (2006) American Medical Association. All rights reserved.]

• References

1) Dowson AJ, Sender J, Lipscombe S, Cady RK, Tepper SJ, Smith R, Smith TR, Taylor FR, Boudreau GP, van Duijn NP, Poole AC, Baos V, Wöber C: Establishing principles for migraine management in primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2003; 57(6): 493-507.

2) Dowson AJ, Bradford S, Lipscombe S, Rees T, Sender J, Watson D, Wells C: Managing chronic headaches in the clinic. Int J Clin Pract 2004; 58(12): 1142-1151.

3) Pryse-Phillips W, Aube M, Gawel M, Nelson R, Purdy A, Wilson K: A headache diagnosis project. Headache 2002; 42(8): 728-737.

4) Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, Tomlinson GA, McCrory DC, Booth CM: Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA 2006; 296(10): 1274-1283.

5) Bigal ME, Lipton RB: The differential diagnosis of chronic daily headaches: an algorithm-based approach. J Headache Pain 2007; 8(5): 263-272.

6) Torelli P, Campana V, Cervellin G, Manzoni GC: Management of primary headaches in adult Emergency Departments: a literature review, the Parma ED experience and a therapy flow chart proposal. Neurol Sci 2010; 31(5): 545-553.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed (2011/10/18)

headache 54858

& diagnosis 32183

& algorithm 170

• Search database: Ichushi Web for articles published in Japan (2011/10/18)

headache 22226

& diagnosis 12004

& algorithm 21

CQ I-9

How is the impact of headache on individuals measured?

Recommendation

Use of questionnaires that have been validated for reliability and validity is recommended to measure the impact of headache on individuals.

| Grade B |

Background and Objective

Impact has a similar connotation to “disability” as defined by the WHO, which is the limitation or incapability of normal activities as a human being. Rather than the subjective manifestation of signs and symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL), the impact of headache is rated as the objective influence of the disease on life activities such as work and leisure activities. Among the primary headaches, the disability caused by migraine has been reported worldwide. The evaluate the severity of migraine, assessing the impact of migraine is important.

Comments and Evidence

Several scales are available for the evaluation of the disability in daily living caused by chronic headache; however, the scales that can be used in Japanese language are limited. This section comments on several questionnaires, including Japanese versions, for the evaluation of the impact of headache in general, which have been reported to have high reliability and validity.

• Headache Impact Questionnaire (HImQ)

This is a scale developed based on the Chronic Pain Inventory (CPI) for measuring the impact of headache. The scale is a 16-item self-administered questionnaire: number of headaches; headache duration; pain intensity; disability; and time lost in work for pay, housework and non-work activities. The scale can be applied to all headaches and has wide utility. However, scoring is complicated, and is therefore more suitable for research than for primary care.1)

• Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS)

This is a brief questionnaire based on a part of HImQ. The MIDAS divides daily living into work or school, household work, and non-work activities. The missed days in work and other activities are scored and the total score is used to evaluate the disability. The scale is useful not only for migraine but also for headache in general.2) The MIDAS has been translated into various languages including Japanese, and the reliability and validity have been evaluated.3)

• Headache Impact Test (HIT)

The HIT is composed of items from several widely used QOL and daily living disability scales with proven validity; the Headache Disability Inventory (HDI), Headache Impact Questionnaire (HIQ), MIDAS, and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ), together with added questions from clinicians and QOL specialists. It is a tool for measuring the impact of headache on individuals in their ability to function on the job, at school, at home and in social situations. The scale is in the form of an internet-administered questionnaire (only available in English).4)

• HIT-6

The HIT-6 was developed through the construction of the HIT. The questionnaire can be administered as a short paper-based test consisting of six questions that can be responded within one minute. The questions are on pain intensity, impact on daily activities, impact on social activities, and mental burden due to headache. The respondent chooses from one of five choices for each question. Each choice has a predetermined score, and the total score for all six questions is calculated. Based on the total score, the impact on daily living is classified into four grades.5) A high correlation has been found between the HIT-6 score and HIT score. The scale has been translated into more than 25 languages. The reliability of the Japanese version has also been validated.6)

• Migraine Work and Productivity Loss Questionnaire (MWPLQ)

The impact of headache can be measured by focusing on productivity at work.7)

• Headache Needs Assessment (HANA)

The HANA is a questionnaire consisting of 7 items that evaluate the frequency of loss of QOL and bothersomeness.8)

• References

1) Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Simon D, Von Korff M, Liberman J: Reliability of an illness severity measure for headache in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Cephalalgia 1998; 18(1): 44-51.

2) Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN: Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 2000; 88(1): 41-52.

3) Iigaya M, Sakai F, Kolodner KB, Lipton RB, Stewart WF: Reliability and validity of the Japanese Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire. Headache 2003; 43(4): 343-352.

4) Bayliss MS, Dewey JE, Dunlap I, Batenhorst AS, Cady R, Diamond ML, Sheftell F: A study of the feasibility of Internet administration of a computerized health survey: the headache impact test (HIT). Qual Life Res 2003; 12(8): 953-961.

5) Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE Jr, Garber WH, Batenhorst A, Cady R, Dahlof CG, Dowson A, Tepper S: A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003; 12(8): 963-974.

6) Sakai F, Fukuuchi Y, Iwada M, Hamada J, Igarashi H, Shimizu T, Suyama K, Kageyama S, Arakawa I, Ijiri T, Uechi Y, Nagata T. Evaluation of reliability of the Japanese version “Headache Impact Test (HIT-6)”. Rinsho Iyaku 2004; 20(10): 1045-1054. (In Japanese)

7) Davies GM, Santanello N, Gerth W, Lerner D, Block GA: Validation of a migraine work and productivity loss questionnaire for use in migraine studies. Cephalalgia 1999; 19(5): 497-502.

8) Cramer JA, Silberstein SD, Winner P: Development and validation of the Headache Needs Assessment (HANA) survey. Headache 2001; 41(4): 402-409.

• Search terms and secondary sources

• Search database: PubMed(2011/8/28)

Headache All fields 54478

& {impact} 1284

& {burden} 94

& {QOL} 32

• Search database: Ichushi Web for articles published in Japan (2011/12/21)

headache 795

& {QOL and/or quality of life}12

& {disability}1

& {burden}0

& {impact}0

CQ I-10

How are questionnaires and screeners used?

Recommendation

Questionnaires on headache include those that measure the disability in daily living, QOL, treatment effect and satisfaction, as well as diagnostic screeners for the diagnosis of migraine. Use of these questionnaires and screeners contributes to routine clinical care by improving the communication between patients and doctors, and providing simple and rapid diagnosis as well as objective evaluation of therapeutic effects.

| Grade B |

Background and Objective

Although a careful medical interview is important for the diagnosis and treatment of headache, it is difficult to obtain sufficient information from patients during the busy consultation hours. Various interview sheets and screeners have been developed to support the routine clinical care for primary headaches, with the objective to attain accurate diagnosis and treatment as well as effective communication between doctors and patients.

Comments and Evidence

The following interview sheets and screeners for headache have been evaluated for reliability and validity.

Diagnostic screeners

(1) 3-Question Headache Screen

(2) ID Migraine

The 3-Question Headache Screen1) diagnoses migraine from three features: (1) recurrent headaches that are disabling (2) headaches lasting at least 4 hours and (3) no new or different headaches in the past 6 months.

The ID Migraine2) diagnoses migraine from three items: disability, nausea and sensitivity to light. Because the screener is simple and can be self-administered, its usefulness in primary care is attracting attention. In Japan also, similar validation study was conducted as a multi-center, blinded, clinical epidemiological study2b).

Questionnaires on disability and severity

(1) Headache Impact Questionnaire (HImQ)

(2) Migraine Work and Productivity Loss Questionnaire (MWPLQ)

(3) Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire

(4) PedMIDAS

(5) Headache Impact Test (HIT)

(6) HIT-6

MIDAS and HIT are examples of short questionnaires.

The MIDAS questionnaire 3)-5) is a short questionnaire developed based on the HImQ. It divides daily living into work or school, household work and non-work activities, and evaluates the degree of disability from the missed days of these activities.3)4) This scale is useful not only for migraine but also for headache in general. It has been translated in various languages including Japanese,5) and the reliability and validity have been evaluated. In addition, MIDAS for adolescents and children, PedMIDAS6) has also been developed and is useful for the evaluation of pediatric headache.

The HIT is composed of items from several widely used QOL and daily living disability scales with proven validity; the Headache Disability Inventory (HDI), Headache Impact Questionnaire (HIQ), MIDAS, and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ), together with added questions from clinicians and QOL specialists. It was developed as a tool for measuring the impact of headache on individuals in their ability to function on the job, at home, at school and in social situations. The scale is only available in English. The test is internet-administered, and evaluates the impact of headache comprehensively.7)

The HIT-68) was developed through the construction of the HIT. The questionnaire can be used as a paper-based test and consists of six questions. The questions are on pain intensity, impact on daily activities, impact on social activities, and mental burden due to headache. There are five choices for each question. Each choice has a predetermined score, and the total score for all six questions is calculated. Based on the total score, the impact of headache on daily living is classified into four grades. The short questionnaire can be completed within one minute. The HIT-6 has been translated into more than 25 languages. The reliability of the Japanese version has also been validated.9)

Questionnaires on patient QOL

(1) Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ)

(2) Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Measure (MSQOL)

The MSQOL10) is a questionnaire consisting of 25 items developed for the evaluation of the QOL of patients with migraine. High reliability and validity have been reported.

The MSQ ver. 2.111) is composed of 14 items on family, leisure activities, daily activities, work, concentration, tiredness, feeling energetic, canceled work or daily activities, needed help, stopped work or daily activities, social activities, frustration, burden, and afraid. The impact of migraine on QOL is assessed by three dimensions: role function restrictive, role function preventive, and emotional function. The Japanese version of MSQ ver 2.1 has also been evaluated for reliability and validity.12)

Questionnaires on treatment

(1) Migraine Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (MTAQ)

(2) Migraine Assessment of Current Therapy (Migraine-ACT) questionnaire

(3) Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire

(4) Headache Impact Test (HIT)

The MTAQ13) is a 9-item questionnaire that requires a response of yes or no to each question. The questionnaire was developed to assess therapeutic effect and identify patients who require changes in treatment.

The Migraine-ACT14) further simplifies the MTAQ. The therapeutic effect and whether the patient need to change treatment can be assessed by answering yes or no to four questions: (1) Does your migraine medication work consistently, in the majority of your attacks? (2) Does the headache pain disappear within 2 hours? (3) Are you able to function normally within 2 hours? (4) Are you comfortable enough with your medication to be able to plan your daily activities? Due to its sensitivity and simplicity, this questionnaire is recommended to be used also in primary care.

Although the MIDAS questionnaire is a tool for evaluating disability, by performing this test before and after treatment, the change in score or grade may indicate the effectiveness of treatment.

For HIT and HIT-6 also, by performing the test before and after treatment, the change in score may indicate treatment efficacy.15)

• References

1) Cady RK, Borchert LD, Spalding W, Hart CC, Sheftell FD: Simple and efficient recognition of migraine with 3-question headache screen. Headache 2004; 44(4): 323-327.

2) Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, Harrison W: A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology 2003; 61(3): 375-382.

2b) Takeshima T, Sakai F, Suzuki N, Shimizu T, Igarashi H, Araki N, Manaka S, Nakashima K, Hashimoto Y, Iwata M, Fukuuchi Y: A simple migraine screening instrument: validation study in Japan. Japanese Journal of Headache (in press).

3) Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Sawyer J: Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score in a population-based sample of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia 1999; 19(2): 107-114.

4) Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN: Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 2000; 88(1): 41-52.

5) Iigaya M, Sakai F, Kolodner KB, Lipton RB, Stewart WF: Reliability and validity of the Japanese Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire. Headache 2003; 43(4): 343-352.

6) Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, LeCates S, Kabbouche MA, Maynard MK: PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology 2001; 57(11): 2034-2039.

7) Bayliss MS, Dewey JE, Dunlap I, Batenhorst AS, Cady R, Diamond ML, Sheftell F: A study of the feasibility of Internet administration of a computerized health survey: the headache impact test (HIT). Qual Life Res 2003; 12(8): 953-961.